In 1923 Noel Skelton, the Scottish Unionist politician and Conservative thinker, wrote that in order to make democracy stable, government needed to promote “a property-owning democracy”. This would be able to meet the rise of socialism with “constructive conservatism”, which would expand and protect the interests of property.

A century later, Skelton’s views on home ownership remain acutely relevant. Among the scores of promises being offered in the current contest to be the next leader of the Conservative party — and thus UK prime minister — are pledges to make it easier for “Generation Rent” to get on to the housing ladder. Both candidates claim to be the true heir to Margaret Thatcher, whose “Right to Buy” policy was one of the defining policies of her long tenure in Downing Street from 1979-90. Very much in the Skelton mode, Right to Buy aimed to create such a property-owning democracy by giving tenants in local-authority housing substantial discounts so that they could buy their own homes.

Today, a combination of house price inflation fuelled by central bank quantitative easing, alongside austerity and the unintended consequences of Right to Buy, has turned that dream on its head. Right to Buy was a remarkable success in that it led to the sale of more than 2mn homes and resulted in an immediate transfer of wealth. But one of its direct, longer-term consequences has been that, rather than increasing home ownership, it contributed to the rapid growth of an under-regulated and precarious private rented sector.

In 1979, more than a third of people in England lived in council housing built, owned and administered by local government. Now, more than 40 per cent of the council homes bought under Right to Buy have been sold on to private landlords, who rent them out at three or four times the price of an equivalent property in the social housing sector. The result is that, in many parts of the country, private renting is unaffordable for those on lower and even middle incomes, excluding people from the market and leading to a continuous cycle of eviction. At the same time, a comparison of 35 European countries ranks the UK among the lowest 20 per cent in terms of home ownership, putting paid to the myth that the British are a nation of homeowners.

A number of new books capture this reality. In a welcome break with the well-worn stereotypes of writing about property and housing — breathless descriptions of accelerating prices or the dead prose of jargon-laden policy briefs — they look instead at the human experience of being forced to move, which has become an ever-present reality that colours daily life for the 11mn people who make up Britain’s population of private renters.

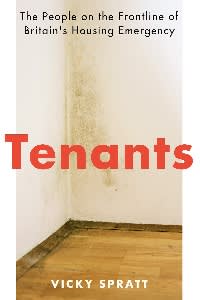

In Tenants, Vicky Spratt’s shocking and incisive indictment of private renting in Britain, she describes how functional and productive lives unravel as people lose their homes, sense of self and feeling of belonging in the world.

The case studies are shocking and sobering. Limarra, with her two degrees and job as a manager, was looking to progress into HR, to provide a secure base for her seven-year-old daughter. When her landlord notified her that he would be selling the south London flat where she had lived for nearly a decade, her life spiralled out of control.

Unable to afford another place, she had to turn to the council for help. But in order to qualify for assistance, she needed to prove that she was not “intentionally homeless”; this meant she had to wait for the landlord to issue her with a possession order through the courts, which took nearly a year. Having to wait to be evicted from her home was so damaging to her mental health that she was signed off work with severe anxiety and depression and was later hospitalised after taking an overdose.

When she was finally offered housing it was outside London, far from her daughter’s school and her mother, her only source of childcare. When she broke down in tears and asked how she would get her daughter to school, the placement officer told her to “get up earlier”. She and her daughter now live with her mother, the two of them sleeping in the living room and joining the ranks of the hidden homeless.

Tenants is packed with powerful narratives but also puts forward a number of policy alternatives. One of these is Housing First, which was developed in New York and which has transformed housing policy in a number of European countries, including Finland, the Netherlands and Austria. The policy, which is now being trialled in the UK, is aimed at the homeless and is premised on the provision of a home regardless of employment or addiction.

But Spratt believes that the guiding principle, of providing secure housing to people, should be extended across the private rented sector. This would help to counter the pernicious effects of the 1988 Housing Act, which introduced assured short-hold tenancies and left Britain with a legacy of allowing some of the shortest lets in the world — at just six months — paralleled only by Australia. Like Spratt’s book, barrister Hashi Mohamed’s beautifully written A Home of One’s Own emphasises the emotional fallout of constantly having to move, describing the sense of helplessness his family faced, with no control over the most significant aspect of their lives.

Living in a state of housing instability overlaps with homelessness, with many people, like Limarra, classed as homeless even though they have a roof — albeit an inadequate one — over their head. Daniel Lavelle’s raw and compelling memoir, Down and Out, brings together precarity in private renting with street homelessness as he details his horrifying and abusive experiences of the care system and his inevitable descent into rough sleeping, addiction and homelessness. Lavelle describes himself as one of the lucky ones, who managed to get out, when many of those close to him didn’t. But even now, as a successful journalist, he has been evicted from two homes by two different landlords and his housing remains insecure.

Finding herself unable to travel due to the pandemic, Sunday Times foreign correspondent Christina Lamb turned her attention closer to home. The Prince Rupert Hotel for the Homeless is the story of how a historic hotel in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, found itself providing the local homeless population with somewhere to live for a year, as part of the government’s emergency “Everyone In” initiative.

Lamb’s compassionate and compelling narrative is heartwarming but doesn’t scrimp on the challenges faced. The family atmosphere unexpectedly created by hotel staff more accustomed to upscale guests sits alongside drug taking in the rooms, ambulances and fights, but the overwhelming message is that when the political will is there to house people, it can and does happen. As Spratt says, the Conservatives’ previous promise to end street homelessness by 2027 was rushed through by “Everyone In” in 10 days.

When Spratt, who is the housing correspondent of the i newspaper, was starting out in journalism, she worked as a junior producer at the BBC. One day she suggested that they might want to run more stories on housing, only to be told dismissively by her editor that “it’s just not that interesting”.

It’s a response I’m familiar with. Embarking on a career in journalism I alighted on housing as a vital social policy area that seemed to receive little coverage. I soon realised why: where once pretty much every newspaper had a housing correspondent, now they were filled to bursting with property supplements. Housing had been relegated to poor housing.

These books reveal a shift away from the property-boom approach to housing. All are based on myriad human stories which show that having a home is a central aspect of people’s lives and a cornerstone of trust in society and its institutions. The shifting nature of the discourse around the housing crisis is significant as, combined with the success of radically different approaches such as Everyone In and Housing First, they herald a real possibility of change.

The narratives also highlight that it’s a change which seems to have permeated the highest levels of government. Michael Gove, until recently UK secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities, lambasted volume housebuilders as operating a cartel with unhappy consequences and condemned the poor quality of much of the private rented sector. In language a world away from more familiar Conservative rhetoric on housing, he repeatedly made it clear that far more social housing is needed — a stance echoed by the opposition Labour party.

Yet, like so many of his predecessors, Gove was only in post briefly, and weakness of leadership at the top is identified as a key barrier, with 12 housing ministers since 2010. There is also frustration that cross-party support for a land value tax, recommended by separate government inquiries by both parties and supported by many economists, has not been taken up. As the housing crisis blights ever more lives, the nature of the debate is shifting fundamentally, but whether the current political climate can action that readiness for change is another question.

Anna Minton is the author of ‘Big Capital: Who Is London for?’ (Penguin) and reader in architecture at the University of East London

Tenants: The People on the Frontline of Britain’s Housing Emergency by Vicky Spratt, Profile Books £20, 352 pages

A Home of One’s Own by Hashi Mohamed, Profile Books £5.99, 160 pages

The Prince Rupert Hotel for the Homeless: A True Story of Love and Compassion Amid a Pandemic by Christina Lamb, William Collins £20, 320 pages

Down and Out: Surviving the Homelessness Crisis by Daniel Lavelle, Wildfire £18.99, 304 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

More Stories

‘The Forest Must Stay!’ Treetop Protest Erupts At Tesla’s Berlin Gigafactory As Activists Try To Thwart Expansion – Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

GamerSafer acquires Minecraft-focused Minehut server community

New York Appeals Court allows Trump, sons to continue running business, denies request to delay payment